By Nadia Lemko

By Nadia Lemko

In the shattered streets of Kherson, where the buzz of Russian drones now replaces the sound of traffic, British–Irish journalist Caolan Robertson stands with a camera in one hand and a flak jacket on his back. “Every day here, people live not knowing if they’ll survive the walk to buy bread,” he narrates in one of his recent short films. For Robertson, these moments are not just footage — they are fragments of history that demand to be witnessed.

From Media Provocateur to War Reporter

Robertson first gained attention years ago for his work in media and documentary production in the UK. In 2023, however, his trajectory shifted dramatically. Citing what he described as a “lack of raw, on-the-ground truth” about Russia’s invasion, he moved to Ukraine full-time to report independently on the war.

Now based in Ukraine he reports about the activities in cities such as Kyiv, Kherson, and Kramatorsk. Robertson produces daily dispatches, investigative videos, and documentaries focused on the human cost of the war. He funds much of his work through Patreon and independent streaming deals, enabling him to operate outside large news networks. “My goal is to document what Russia is trying to hide — the war crimes, the terror, the day-to-day survival,” Robertson writes in his project statement.

Under Deadly Skies: Ukraine’s Eastern Front

Robertson’s 2023 documentary Under Deadly Skies, co-directed with veteran journalist John Sweeney and war photographer Paul Conroy, captures Ukraine’s eastern front in forensic, often disturbing detail.

Filmed near the front lines around Bakhmut and Kramatorsk, the film investigates Russian war crimes — including torture, cluster munitions, and the systematic targeting of civilians. The camera lingers not only on the bomb craters but on the survivors: farmers, mothers, and soldiers who speak through the thunder of shellfire.

Critically recognized for its unfiltered perspective, Under Deadly Skies was screened internationally and praised for its “forensic humanity” — offering not just documentation of violence but testimony of endurance.

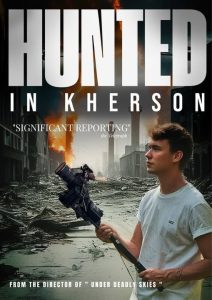

Hunted in Kherson: Life Under Drones

In his follow-up film Hunted in Kherson (2024), Robertson turns his lens southward to the city of Kherson, liberated yet constantly under siege. The documentary, produced for Journeyman Pictures, depicts a haunting new phase of warfare: drones hunting civilians.

Through interviews with residents, the film shows a city where even daylight feels unsafe. People run errands at dawn — the brief window before drone flights begin. “We go out unsure if we’ll live,” one resident tells Robertson as the distant hum of engines fills the sky.

The film illustrates a grim shift in Russian tactics, using small drones to drop grenades on cars, homes, and aid workers — a campaign Robertson describes as “psychological warfare designed to break people, not just buildings.”

The Farmers of Kherson: Tilling Land, Under Fire

Robertson’s latest documentary The Farmers of Kherson delves into the little-seen world of agriculture under war. Focusing on the late Ukrainian farmer Oleksandr Hordiienko, the film portrays how the occupation, mining of fields, drone attacks and everyday elements of warfare have turned one of Ukraine’s most fertile regions into a battleground.

Hordiienko, his family say, cleared thousands of hectares of mines, shot down over 200 Russian drones with anti-drone rifles, and risked his life caring for the land and his workers — all of which Robertson uses to illustrate the broader impact of war on Ukrainian food production and rural life.

Kramatorsk and Kyiv: Fragile Normalcy Amid War

Robertson’s other reports from Kramatorsk chronicle the aftermath of a missile strike that hit a crowded pizzeria in mid-2023 — a popular meeting place that symbolized fragile normalcy. In a Byline Times article titled There Are No Shelters in the Storm, Robertson wrote that the attack revealed how “safety in Ukraine is an illusion; nowhere is beyond reach.”

In Kyiv, his coverage moves between missile aftermaths, civilian resilience, and the mental toll of two years of unrelenting war. His videos often feature the quiet determination of Ukrainians rebuilding homes, teaching children, or tending to fields under the shadow of air raids.

Independent Journalism at a Cost

Robertson’s approach to war reporting is raw, self-funded, and personal. Without a network’s infrastructure or security, he relies on local contacts, protective gear, and his own judgment to navigate frontline zones. His independence allows creative freedom, but it also carries risk.

Despite occasional criticism of his earlier career in British media circles, Robertson’s Ukrainian work has earned respect among journalists and NGOs for its immediacy and courage. His footage has been used in rights-monitoring projects and screenings documenting civilian harm and alleged war crimes.

Bearing Witness

In his most recent Facebook and YouTube reels filmed in Kherson’s battered neighborhoods and the trenches outside Kramatorsk — Robertson’s tone is both intimate and defiant. “This war isn’t happening in the abstract,” he says in one clip. “It’s happening to people. Ordinary people, in homes just like yours.” As the war grinds on, Caolan Robertson’s work stands as a reminder of journalism’s oldest duty: not only to inform, but to bear witness — even under deadly skies.