During the years 1995-2021, archaeologists and historians from Chernihiv University in Ukraine and the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) at the University of Alberta conducted annual excavations in the town of Baturyn, Chernihiv Oblast (fig. 1). This archaeological research was suspended in 2022-23 following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. However, with funding from CIUS, associates of the Hetman Capital National Historical and Cultural Preserve resumed excavations in Baturyn last summer (fig. 2).

During the years 1995-2021, archaeologists and historians from Chernihiv University in Ukraine and the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) at the University of Alberta conducted annual excavations in the town of Baturyn, Chernihiv Oblast (fig. 1). This archaeological research was suspended in 2022-23 following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. However, with funding from CIUS, associates of the Hetman Capital National Historical and Cultural Preserve resumed excavations in Baturyn last summer (fig. 2).

This article summarizes the architectural and archaeological investigations of the remnants of the principal residence of Hetman Ivan Mazepa in Baturyn for many years, and compares it with similar early modern structures in the West (figs. 7-15).

The Canada-Ukraine Baturyn Archaeological Project is administered by The Peter Jacyk Centre for Ukrainian Historical Research at the CIUS Toronto Office (https://www.ualberta.ca/ canadian-institute-of-ukrainian-studies/centres-and-programs/jacyk-centre/baturyn-project.html). Prof. Zenon Kohut, a former CIUS director and an eminent historian of the Cossack state, initiated this project in 2001, and he is currently its academic adviser and the co-author of our publications. Archaeologist Dr. Volodymyr Mezentsev, research associate at CIUS in Toronto, is the project’s executive director. Archaeologist Yurii Sytyi of the Hetman Capital National Preserve leads the Baturyn excavation team (fig. 2).

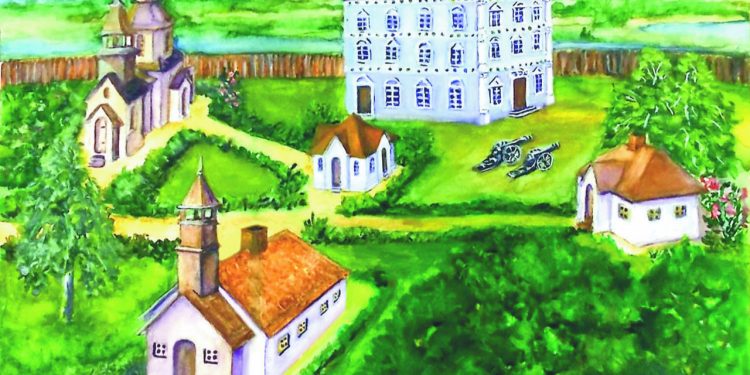

To the present, Baturyn has been fortunately spared Russian bombardment and war destruction. Its five museums of antiquities, as well as the reconstructed citadel, hetman palaces, court hall, and churches from the 17th to 19th centuries have been safely preserved (fig. 1).

In 1669, Baturyn was appointed the capital of the Cossack realm, or Hetmanate. The town experienced its peak under the reign of Hetman Ivan Mazepa (1687-1709), a prominent statesman, patron of culture, and benefactor of numerous churches and secular structures in Ukraine (figs. 3, 16).

In 1708, Mazepa, allied with Sweden, raised the revolt for the liberation of Central Ukraine from Moscow’s autocratic rule. That year, the army of Tsar Peter I, with the aid of a traitor, seized the rebellious Baturyn. Russian punitive forces brutally executed the captured Cossacks and state officials, massacred the entire civilian population, up to 14,000 Baturyn residents, and looted and burned the town. With such ruthless terror, the Tsar suppressed Mazepa’s anti-Moscow uprising, punished the rebels, and demoralized the supporters of the unsubmissive hetman and all of Ukraine.

Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovsky (1750-64) rebuilt Baturyn from the ruins, repopulated, and reinstated it as the capital of the Cossack polity. However, after its abolition by the Russian Empire in 1764, and particularly following the death of the last hetman in 1803, the town declined and turned into an agrarian settlement while Ukraine remained stateless.

During Ukraine’s independence, thanks to the strong, multifaceted support of President Viktor Yushchenko, the 25-year long archaeological research at the Baturyn terrain, the large-scale on-site reconstructions of the ruined hetman palaces, churches, mansions, and fortifications funded by the state, and the dedicated efforts of the local Historical and Cultural Preserve, the image of the hetman capital was recreated for scholarship, popularization, and the patriotic education of Ukrainians (fig. 1). Even during the turbulent war years, thousands of tourists from Ukraine and abroad continue to visit the restored capital of the Cossack state, with nearly 40,000 visitors last year alone.

Before 1700, Mazepa commissioned his largest estate with a brick palace in Honcharivka, the suburb of Baturyn (figs. 4-7). The bastion fortifications of this principal residence of the hetman were modeled on the advanced fortresses of 17th-century Holland.

While ravaging Baturyn in 1708, tsarist troops plundered and burned Mazepa’s palace. In 1995, and 2003-13, our team excavated its remnants almost completely. To date, this manor is the most extensively archaeologically studied hetman residence in Ukraine.

Archaeologists have established that the basement of the Honcharivka palace had a close to square main section (15 x 14.5 m), divided into four vaulted chambers (fig. 5). From the north, it was adjoined by a brick rectangular compartment (12 x 5 m) with stairs descending to the basement. The above-ground part of this annex likely housed a wooden staircase leading to the upper floors of the palace. Including this extension, the palace was about 20 m long and 14.5 m wide. For Central Ukraine of Mazepa’s era, this was a large residential building.

Based on a 1744 drawing of the ruins of the Honcharivka palace, which is preserved in the National Museum in Stockholm, and the materials found during excavations of its debris, V. Mezentsev has prepared a hypothetical reconstruction of the structure’s exterior before its destruction in 1708 (figs. 3, 7). According to his reconstruction, it had three above-ground storeys with beam ceilings, a mansard, and a vertical spatial composition. Along with the vaulted basement and mansard, the palace had five levels. Perhaps, the roof was hipped with two slopes.

The main façade was crowned by a tall triangular baroque pediment with sloping concave wings and a large window in the mansard. The pediment was flanked by corner pillars with volutes (spiral scrolls) on both sides. The corners of the front elevation on each floor were adorned by brick columns or half-columns on high plinths/pedestals, topped with the capitals of the Corinthian order. Fragments of these capitals with volute reliefs carved in limestone have been discovered (fig. 6). The capitals symbolically supported the entablatures with profiled cornices separating each floor.

In the centre of the main façade was the entrance, framed by a portal with a baroque tympanum. There were three rectangular windows along the front elevation of each of the second and third floors. Presumably, four similar windows were positioned on every tier and mansard of the longitudinal façade. All of the windowsills were decoratively supported on both ends by low ceramic corbels. The window frames were surmounted with triangular and arched crowns or sandriks.

This architecture and the outer ornamentation with classical order elements of Mazepa’s principal residence in Baturyn belong to the Central European baroque style. However, the archaeological findings have revealed that its Western exterior adornments were supplemented by rows of glazed ceramic multicoloured discs featuring rosettes along the friezes of the palace’s entablatures (fig. 7). The pattern recalls the ornate embellishments on the façades and domes of brick churches, belfries, and refectories of Kyiv’s monasteries from the 17th-18th centuries. Except of the Honcharivka villa, this Kyivan decor is unknown in residential structures in Ukraine and baroque architecture across Europe. Yu. Sytyi believes that all of the plentiful, imposing, and expensive majolica façade rosettes, ceramic slabs bearing Mazepa’s coat of arms, and stove (kakhli) and floor tiles of that palace were produced by the best Kyivan artisans. This edifice housed the personal quarters of the hetman and his wife, Hanna (†1702), the state/military and their private treasury, the general chancellery, the archives, the library, and a hall for receptions and banquets.

The reconstructed ground plan, dimensions, vertical three-story superstructure with a mansard, and outer ornamentation of Mazepa’s principal residence in Baturyn resemble relatively small masonry aristocratic palaces, villas, mansions, and monastic buildings of the Polish Kingdom in the 16th to 18th centuries (cf. figs. 7-11, 13, 14). There and throughout Western Europe, between the 14th and 16th centuries, residential towers or tower halls within the manors of feudal lords, magnates, and kings were common.

For example, this type includes the Gothic rectangular three-tiered “Masonry Tower” from the 16th century, the residence of the Ostroh princes of Volhynia, located in the bailey of their castle in the town of Ostroh, Rivne Oblast, Ukraine (fig. 8). Comparable to the Honcharivka palace in terms of parameters, layout, vertical design, numbers of floors and windows, and functions, is the brick residence of Polish King Sigismund I the Old in the town of Piotrków Trybunalski, Łódź Voivodeship (figs. 9, 10). It was constructed in the Gothic-Renaissance style in 1519. This edifice has a vaulted basement (18 x 20 m) and three floors with wooden ceilings. It housed the king’s private quarters, rooms for his attendants and senators, the royal treasury, archives, and a hall.

In the 16th century, Italian architects and decorators rebuilt the medieval castle of the Polish kings on Wawel Hill in Kraków into a secular palace in the late Renaissance style. They erected there a comparatively small tower-like three-story structure with the so-called “Upper Gate” leading into the inner courtyard of the complex (fig. 11). The second and third levels of this gatehouse were part of the royal apartments. The classical portal of the gate is flanked by Corinthian half-columns supporting the entablature.

These relatively small 16th-century tower-like residences of Polish kings can be considered Renaissance prototypes for the architectural design of Mazepa’s baroque palace constructed a century later. While studying at the Kraków Academy or during his service as a courtier for Polish King John II Casimir in the 1650-60s, the future hetman probably saw the edifice with the “Upper Gate” leading to the bailey of the famous Wawel Castle.

In 1659, together with the envoys of the Polish king, the young Mazepa visited Paris and attended a reception at the French royal court in the Louvre in celebration of the signing of the Pyrenees Peace Treaty between France and Spain. At that time, the bedrooms and offices of French King Louis XIV and his distinguished prime minister, Cardinal Jules Mazarin, as well as the salons for court ceremonies, meetings, and audiences with envoys, were located in a comparatively small Royal Pavilion (“Pavillon du Roi”) within the Louvre palatial complex (fig. 12). This tower-like pavilion, four stories high and almost square, was built in 1556 in the style of the Renaissance palazzos in Rome. Its southern façade, facing the Seine River, had a composition and decor somewhat similar to the front elevation of the Honcharivka villa. This façade of the Royal Pavilion was also three windows wide and was crowned with a classical triangular pediment. Each story was separated by entablatures. On the second level, rectangular windows were topped with triangular sandriks, while on the first floor the windowsills were supported by corbels on both sides.

At the mid-17th-century Louvre, Mazepa could have seen the Royal Pavilion described above as well as the Grand Gallery, which was later greatly expanded. Erected in 1610, it was modeled after the late Renaissance palatine galleries of Florence, Italy, from the 16th century. The design of the narrow end face of the Grand Gallery from the early 17th century with its central entrance, triangular pediment, and columns articulating each of its three stories, along with the surmounting of the rectangular windows with triangular and arched sandriks, resembles the reconstruction of the main façade of the Honcharivka palace.

Mazepa’s contemporary, the most prominent architect of Polish baroque, Tylman van Gameren, was the creator of two comparatively small three-tier brick palaces with vertical volume in Warsaw that were commissioned by magnates Adam Kotowski (1684) and Jan Gniński (1685). They preceded the construction of the hetman residence at Honcharivka and were to some extent comparable to its recreated ground plan, dimensions, architectural design, and the composition of the front elevation. The Gniński palace, rebuilt after its destruction in 1944, is also referred to as the castle of Prince Ostrogski in Warsaw (fig. 13).

The Kotowski palace, which was also ruined in 1944 and never rebuilt, had a square layout, a basement with vaulted chambers, three above-ground floors with beam ceilings, a hall on the upper level, and a staircase in a side compartment. Both palaces featured similar risalits (avant-corps), which protruded from the planes of the main façades and were crowned by triangular classical pediments. These risalits had central entrances, three windows on each of the second and third stories, and were articulated by order elements with entablatures, likewise the solution of the front elevation of the Honcharivka villa. However, instead of columns, the risalits of these palaces were finished by pilasters with capitals and pedestals. The fashionable and relatively small baroque palaces of Kotowski and Gniński-Ostrogski from the 1680s in Warsaw, the pieces of high European standard by the most popular architect of that time in Poland, T. Gameren, may have been known to Mazepa or his architect, particularly from illustrated publications. They could have served as the primary sources of inspiration for the design of the hetman principal residence in the following decade.

An analogy to the Honcharivka palace among the more simply decorated monastic buildings in Warsaw is the late-17th-century masonry rectangular edifice adjacent to the Carmelite Church of 1681. Originally it was part of the monastery belonging to this order, which, at that time, existed near the basilica.

This structure has preserved baroque architectural forms and adornments (fig. 14). It has three stories, a basement, and a mansard, the most ornate front-end façade with the entrance in the centre, three rectangular windows on each of the second and third floors, and four windows on each upper tier of the longitudinal elevation, similar to the reconstruction of Mazepa’s palace.

As in the latter, corbels support the sides of all windowsills of this monastic building. Its main façade is topped by a triangular baroque pediment with a window overlooking the mansard level and volutes flanking the sides, while the middle window of the second floor is framed by a triangular sandrik above. Thus, by its size, the numbers of tires and windows, baroque architectural design, some outer ornamental details, and the construction date, this monastic building in Warsaw resembles the recreated Honcharivka palace.

The vertical symmetrical composition and exterior decor of its front elevation were widely used in early modern secular architecture throughout Europe, from Ukraine to Britain. Analogous designs were applied to the end facades and especially to the risalits of numerous masonry and wooden palaces, villas, mansions, town halls, and other civic edifices from the 16th to 18th centuries.

For instance, besides the aforementioned small Kotowski and Gniński palaces, similar three-story risalits, three windows wide with a central entrance and triangular classical pediment, are also present in the larger magnate palaces of Tepper (1685) and Czapski (1686, fig. 15) in Warsaw, the royal palaces of Het Loo (1686) in Apeldoorn, the Netherlands, and Kensington (1689) in London, the Philippsruhe castle (1700) near Hanau, Germany, the palaces of the princes Vyshnevets’ky in the borough of Vyshnivets’ (1730s), Ternopil Oblast, and Sanhushki (1754) in the town of Iziaslav, Khmel’nyts’ka Oblast, as well as the residence of the metropolitan of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in the city of Lviv (1762). In the 1650-60s, the young Mazepa travelled and studied at universities in Germany, Holland, France, and Italy. He had the opportunity to see firsthand the magnificent aristocratic baroque palaces and villas there and to be inspired by their architecture and embellishments.

During his reign, Polish, German, Italian, and Latin books, as well as French and Dutch newspapers, were brought to Baturyn. He followed current events abroad. From his extensive court library and artistic collection in Baturyn, the hetman could have selected and provided the designers and decorators of his residence at Honcharivka with illustrated publications containing examples of fashionable and remarkable baroque palaces and villas in the West.

Thus, this research demonstrates Mazepa’s awareness and appreciation of European culture and art, and his introduction of advanced baroque palatial architecture and decor to the Cossack capital. This comparative analysis of the best archaeologically studied principal residence of the hetman in Baturyn also shows that it was a valuable and unique specimen of the hitherto little-known palatial art of the Hetman state, where the stimulating influences of Western architecture were most vividly manifested. The devastating razing of Baturyn by Russian troops in 1708 permanently ended the development of palaces of this kind in the architecture of Central Ukraine and suspended monumental masonry construction in the town for 80 years.

These authors have examined the topic of this article in more detail in a nicely published and richly illustrated booklet for the general public and scholars titled Архітектура палацу Івана Мазепи у Батурині та західні аналогії (The Architecture of Ivan Mazepa’s Palace in Baturyn and Western Analogies), Toronto: “Homin Ukrainy”, 2024, 36 pp. in Ukrainian, 37 colour illustrations (fig. 3). This thirteenth issue and earlier brochures of the Baturyn project series are available for purchase for $10 from the National Executive of the League of Ukrainian Canadians (LUC) in Toronto (tel.: 416-516-8223, email: [email protected]) and from CIUS Press in Edmonton (tel.: 780-492-2973, email: [email protected]). These booklets can also be purchased online on the CIUS Press website (https://www.ciuspress.com; https://www.ciuspress.com/product-category/archaeology/?v= 3e8d115eb4b3). Their publications were funded by BCU Foundation (Bohdan Leshchyshen, chair) and Ucrainica Research Institute (Orest Steciw, M.A., president and executive director of LUC) in Toronto.

On 25 April 2025, V. Mezentsev presented a public lecture with slides on the topic of this article at Old Mill Toronto, which is available on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4CxrKBWU2K0).

Since 2001, CIUS and Ucrainica Research Institute have sponsored the Canada-Ukraine Baturyn Project. The Ukrainian Studies Fund in New York (www.ukrainianstudiesfund.org) also provides annual subsidies for this project. In 2024-25, the research on the history and culture of the hetman capital and the preparation of associated publications were supported with donations from Ucrainica Research Institute, LUC National Executive (Borys Mykhaylets, president), LUC – Toronto Chapter (Mykola Lytvyn, president), BCU Financial (Andrew Tarapacky, board chair), Ukrainian Credit Union Limited (Taras Pidzamecky, CEO), Prometheus Stefan Onyszczuk and Stefania Szwed Foundation (Mika Shepherd, president), and Benefaction Foundation in Toronto. The most generous individual benefactors of the Baturyn study are Olenka Negrych, Dr. George J. Iwanchyshyn (Toronto), Michael S. Humnicky (Murfreesboro, TN), and Dr. Maria R. Hrycelak (Park Ridge, IL).

Archaeologists are preparing for new excavations in Baturyn in July. They kindly appeal to Ukrainian organizations, foundations, businesses, and individual donors in North America to continue their vital support for the historical and archaeological investigations of Mazepa’s capital and the publication of their findings. Canadian citizens are invited to mail their cheques with contributions to: Ucrainica Research Institute, 9 Plastics Ave., Toronto, ON, Canada M8Z 4B6. Please make your cheques payable to: Ucrainica Research Institute (memo: Baturyn Project).

American residents can send their donations to: Ukrainian Studies Fund, P.O. Box 24621, Philadelphia, PA 19111, USA. Cheques should be made payable to: Ukrainian Studies Fund (memo: Baturyn Project). These Ukrainian institutions will issue official tax receipts to all donors in Canada and the United States respectively.

All institutions and individual donors will be gratefully acknowledged in related publications and public lectures. The benevolent support of Ukrainians in Canada and the U.S.A. will enable the further research on the history and culture of the hetman capital despite the challenges of wartime in Ukraine. For additional information about the Baturyn project, please contact Dr. Volodymyr Mezentsev in Toronto (tel.: 416-766-1408, email: [email protected]).

Prof. Zenon Kohut

Dr. Volodymyr Mezentsev

Yurii Sytyi