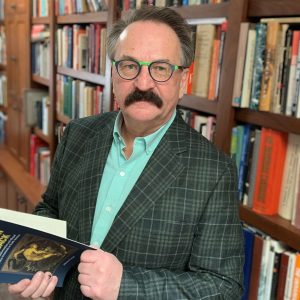

Lubomyr Luciuk

Lubomyr Luciuk

Nov 17, 2025

It’s not exactly a yellow brick road. The journey to the other side begins when you step off a nondescript curb and onto a pathway of concrete paving stones, light grey in colour. Soon, a dark-green mesh fence surrounds you, funnelling you toward the first of two customs booths – the Polish one. Once you clear it, you enter a tunnel-like stretch of footpath, then an open-air section. This is a no man’s land, a neutral zone. Here, I spotted a squad of 8–9 lads, all fit, of a military bearing and buzz cuts, leaving Ukraine. They couldn’t be Ukrainians; men of their age and fitness are obliged to stay to defend their country. They stared as we passed on opposite sides of the separated “in” and “out” lanes. They were as curious about me as I was about them.

Looking back over my shoulder, I saw a large bilingual billboard. It reminded me that I had just left the EU. Ahead lay Ukraine, still being kept at the EU’s edge, conveniently defending Europe’s gates. This world is not fair, I mused.

About fifty metres farther along is the second customs booth, the Ukrainian one. Here, the pathway is a smooth black asphalt. The fencing is blue-tinted and adorned with yellow tridents, the tryzub, Ukraine’s national symbol. Razor wire garnishes this barrier—nasty stuff I remember from a personal encounter in the zone between still-free Georgia and the Russian-occupied South Ossetia.

Walking about 700-800 metres from Medyka to Shehyni—a few minutes’ exercise—I took myself out of today’s Europe and into Ukraine at metre 588, passing from a region of peace into a place at war. Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014, and I came here last in 2017. Since 24 February 2022, the genocidal intensity of Moscow’s war against Ukraine and Ukrainians has escalated, as I would soon witness. This made my situation feel dramatic—but it was also rather prosaic.

The drive into Lviv takes about an hour. I had never been on this highway. It was an unexpectedly warm and sunny autumnal day. Along the way, the influence of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic faith on eastern Galicia’s landscape was in evidence. On the horizon, sunlight glinted off gilded church domes, blessing unseen settlements. For my handler, these visions were commonplace; for me, they were magical.

There are other memorials along this highway, honouring the men and women who defended their homeland against predatory neighbours, before, during and after the Second World War. Whether in the ranks of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists or the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, these locals fought into the 1950s. Their courage is remembered in towns like Mostyska and Zhovkva, and I was told, on monuments found in many communities throughout the region. The Ukrainians I spoke to don’t care whether foreigners share their respect for these nationalists. When I asked why, they replied: “There are those who regard the IRA, or the PLO, or the Irgun, or the Polish Home Army, as heroes. Others brand those very same groups as villainous. We’ll write Ukrainian history as we see fit, not have it dictated to us by our nation’s foes.”

Then we reached the suburbs of Lviv. Just hours earlier, on 5 October, a Russian missile struck the neighbourhood of Lapaivka, in the Zymna Voda district. A family of four was murdered in their home, in the dead of night. As we drove by, the ruins were smouldering, with emergency vehicles and first responders on scene. I thought of all the reminders of past conflicts I’d seen between this tragic site and the borderlands and of how Ukraine is yet again suffering savagery at the hands of a historic foe. What is happening nowadays will not be forgotten soon, if ever. Let me assure you: Russia’s time for atonement is coming. And Putin’s penance will be capital.

I spent several days in Lviv and witnessed the shared purpose and fortitude of its residents. Ukrainians don’t have to go anywhere to find the brains, courage, or heart they need to secure victory. The antics of a trimmer like Trump or the skulduggery of the fake wizard of Z, chortling away behind the Kremlin’s curtains, are disquieting. But such distractions won’t stop Ukrainians from appreciating a cardinal fact: there’s no place like home. Ukraine is theirs, and they won’t give it up. Anyone who listens to their national anthem knows how it affirms, repeatedly: “Ukraine has not perished.” It never has. It never will.

Lubomyr Luciuk is a Professor Emeritus of The Royal Military College of Canada and a Senior Research Fellow of the Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto.